Photography, it seems, has always been “there” in my mind, in my life.

When I was a very small boy I found a dusty box of my dad’s darkroom gear in the cluttered attic of our house. I was fascinated by it even though I had no clue what any of it was for, I suppose it reminded me of our chemistry set1. Occasionally we’d go stay at my nana’s house–my dad’s mum–and I slept in the back bedroom where there was a sink. I knew that dad had used that room, and that sink, to develop pictures back in the 1950s. It all seemed like some mysterious alchemical art, and an interesting part of who my dad was.

Back then he would have been using a Kodak Six-20 “Brownie” D box camera before later stepping up to a German-made folding Agfa Isolette 6x6 camera. By the time I came along he was no longer processing his own film (hence the dusty box in the attic) but that Agfa was still around and it was magical, to me. This slim elegant device that, with the press of a small button, opened itself and unfolded a technical looking lens and bellows arrangement from within. It felt like you were waking up the camera. (If you’re old enough to remember, it had the same fascination, for me, as soft-opening cassette tape decks). You couldn’t press the shutter release until you’d ‘cocked’ the lens. It was all so mechanical.

I think I’ve loved “art” for as long as I can remember, but art that also requires some physical craft, some gear knowledge? Sign me up forever.

According to my brother, Chris, our late uncle David gifted him a Kodak Brownie 127 camera, further increasing the photographic footprint in our household. Then there was a promotion with Ty-phoo tea, which we drank by the gallon in our house; save enough tokens from packets of tea (loose leaf, of course, we weren’t heathens with bags2) and you got a free new camera. So Chris saved up the requisite number of tokens and sent them off with a postal order for postage and packaging and–”allowing 28 days for delivery”–received a Kodak Instamatic 32 camera in the post. That Instamatic, launched in 1972, seemed so modern. It used funky 126 format film cartridges, and disposable revolving cube flash bulbs–actual bulbs, that actually blew, with each shot, four shots per cube, toss in the bin.

So I got the hand-me-down Kodak Brownie 127. It seemed so archaic, in comparison to the Instamatic, but I didn’t care, I had my own camera for the first time. I couldn’t wait to have my own rolls of film and make my own pictures with it.

The Brownie 127’s were first produced by Kodak UK in 1952 and millions of them were made between then and 1959. The first version (there were 3 in total) had a plain face plate around the lens, in 1956 the face plate was changed to the cross hatched version you see in the picture, so mine is likely close to 70 years old, now. The 127 film format was an even older creation, dating all the way back to 1912. It’s bigger than 35mm but smaller than 120 with a film width of 46mm and in my Brownie it produced an image size of 60mm x 40mm. That’s a lot of negative area for such modest camera. It was as simple as could be with just a film wind-on knob and a shutter release. With no focusing and no shutter speeds it was true point and shoot3. Even the wind-on knob had zero sophistication, no latching, nothing to tell you when it was wound on, nothing to do except to look through the little, red, round window, on the back of the camera, and wait to see the next number appear on the backing paper of the film.

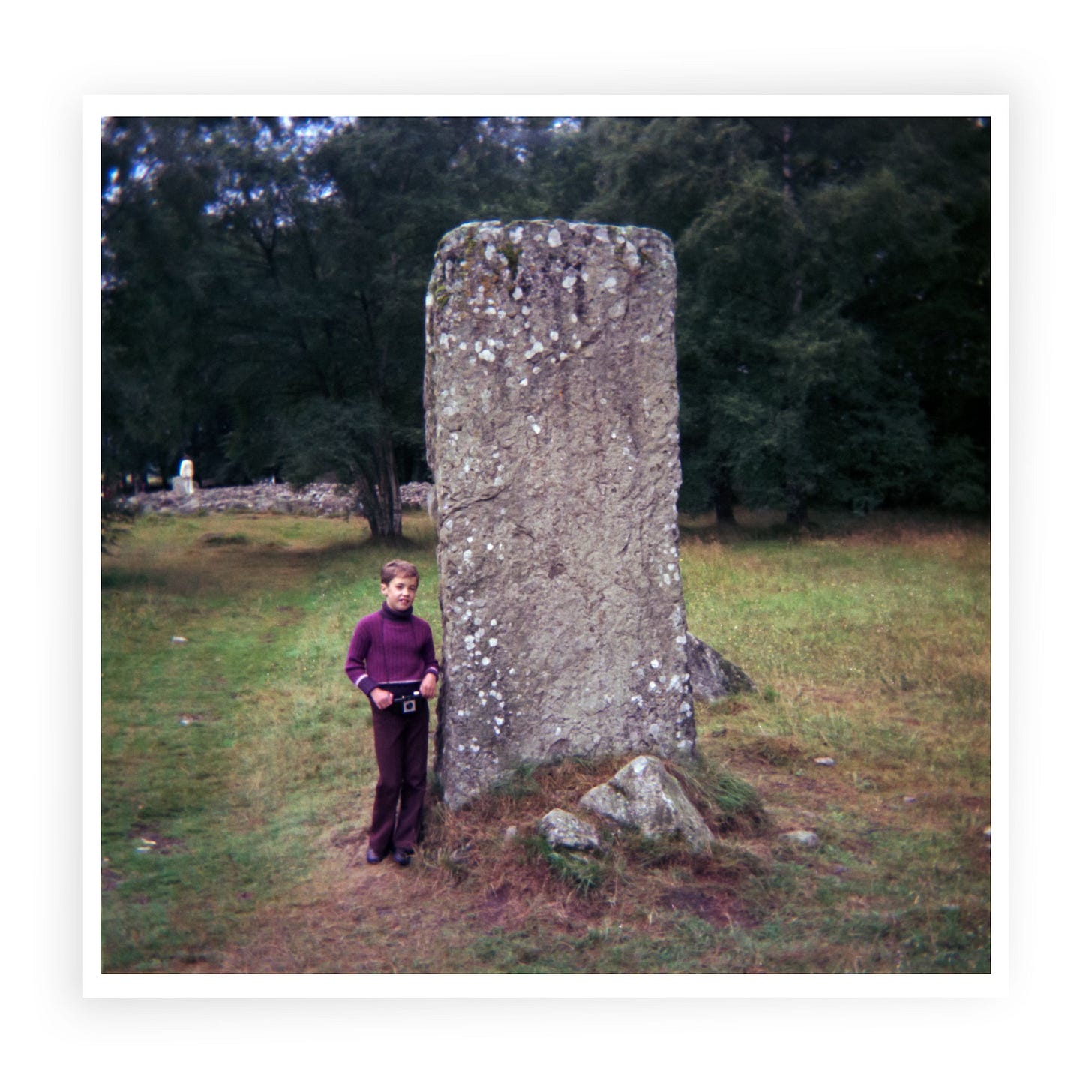

In August 1975 our small family sallied forth to Scotland for a driving tour of the “Highlands and Islands”. My dad worked on the railway, at the time, so we had free passes to take the train from Nottingham all the way to Inverness. There we picked up a shiny new Ford Escort rental car–we had never had a brand new car–and spent the next two weeks traversing Scotland. It’s all a bit of a blur, it was fifty years ago, after all. And, of course, our parents are no longer around to ask. But we drove down the Great Glen, along the side of Loch Ness, we drove through places with amazing names like Drumnadrochit4 and Fort Augustus, Invermoriston and Achnasheen. We eventually made it all the way to Portree, on the Isle of Skye, where we stayed at a B&B with an enormous vat of salted porridge permanently bubbling on the stove. And there was a wooden log holding up one corner of the living room sofa.

I know it sounds like just a regular family driving holiday but this trip signifies my photographic beginnings, my visual awakenings, perhaps.

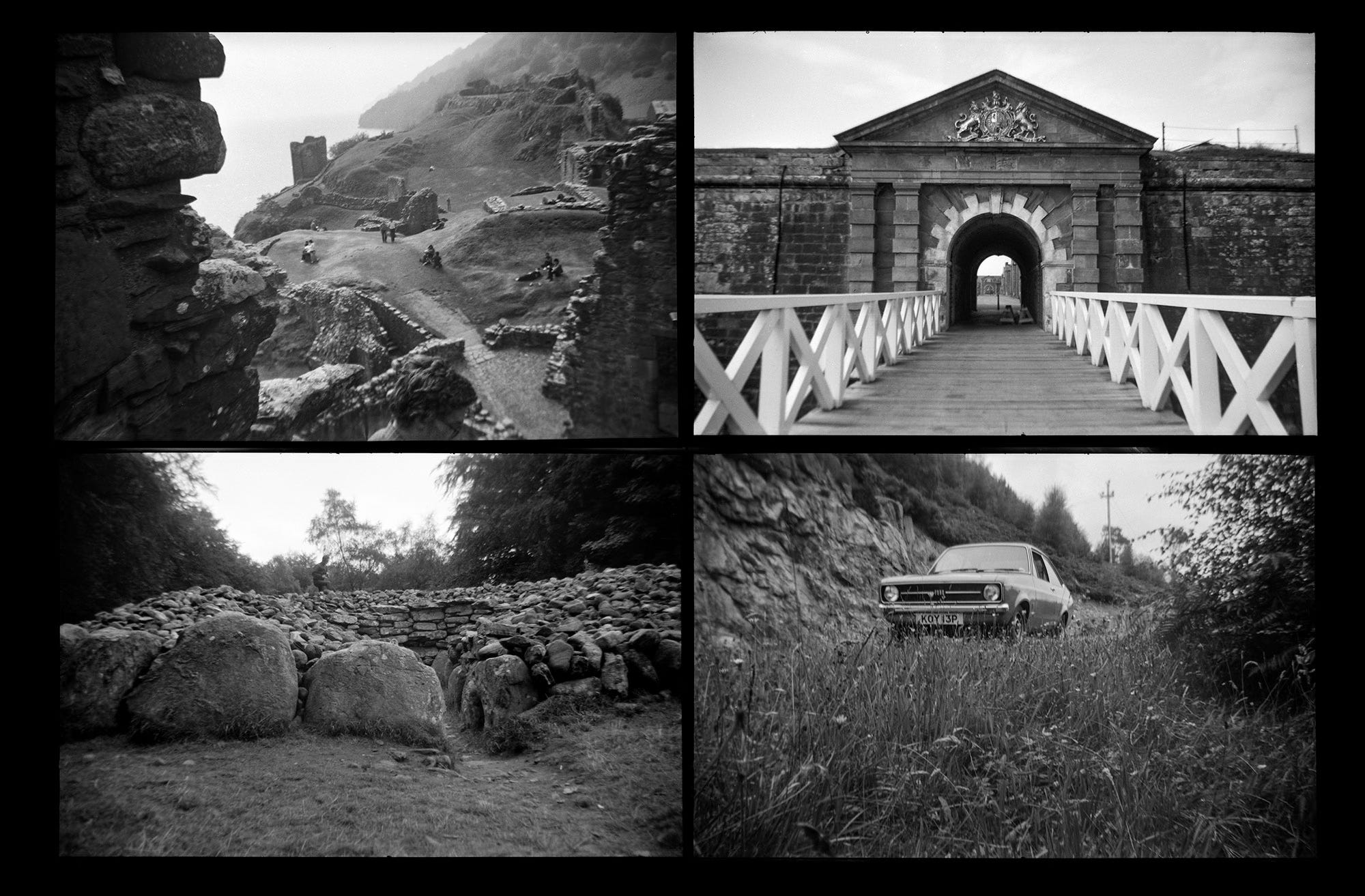

I shot my first two rolls of film with the Brownie 127, on that trip to Scotland, fifty years ago this month. I was only 8 years old so I couldn’t have articulated the feeling but there was something going on in my mind. Looking back I realize that I had some intention in what I was doing. I remember the feeling of trying to make pictures, the realization that this was my camera, my two rolls of film, and that I had but sixteen button pushes to last for two weeks. You can even see, in the details at the top of this essay, that I was experimenting with orientation, I think I was looking at everything through that little plastic viewfinder.

“Photography is about finding out what can happen in the frame. When you put four edges around some facts, you change those facts.”

Garry Winogrand

I still have the negatives of those two rolls of film and perhaps even more surprisingly 3 or 4 of the frames are recognizably “me”, pictures that I can look at now and recognize the way I still see things. It’s my juvenilia but it’s definitely me. Looking at my dad’s and my brothers’ pictures from the trip, I was often shooting when they shot, but not always shooting the same way that they shot.

Also, when I reflect on the picture, below, taken by my dad, I realize that three out of the four members of our family had cameras5 which seems, perhaps, unusual for the time. These days, of course, every member of a family would have some kind of camera and several social media outlets poised to receive a steady flow of digital imagery. It should also be noted that I still have, in my possession, all three cameras involved in this particular photograph.

Shortly after the Scotland trip my dad got a Zenit E SLR camera, and started shooting 35mm film. Then he had an EM which got stolen, and then a Zenit TTL camera made in 1979 (you can see the 1980 Moscow Olympics logo on the pentaprism housing, below).

In 1982 I took my first steps into the world outside of England, on an educational school cruise around the mediterranean, and my dad let me take his Zenit TTL camera, along with 4 rolls of 35mm film. I loved shooting with that camera. My friend Eric and I were the only two kids in our class who had “proper” cameras, he had a Minolta. This trip–which deserves its own essay–ignited my desire to see the world with a camera in my hand.

My brother, being older, and having some of his own money, got himself a fancy looking Chinon CE-4 from Dixons, around this time, and all I had was a collection of crappy 35mm and 110 compacts that I picked up here and there, in junk shops and the like.

But in January of 1986, just after my 19th birthday, I went to the Jessop’s camera shop, signed up for their in-store credit, and spent £338.85 on a Nikon FG, a couple of lenses, and a Vivitar flash gun. There have been many, MANY cameras, since then, and most of them have been Nikons. There’s been some medium format stuff, too, film and digital; Bronica, Hasselblad, Mamiya, Pentax…

So, here we are, exactly fifty years since that trip to Scotland and a curiosity, sparked by my dad and his interest in photography, still burns within me. He always refused to take any credit (or blame!) but it did all start with him.

There have been times when photography has drifted out of the viewfinder of my life, times when I had no clue what I was doing, even times when I felt like I hated it, or even worse, that it hated me. But photography has always fascinated me, as an art form, as journalism, as a technical craft, and as a cultural phenomenon. Over the years I’ve studied the history of the art, the science, the craft, and the work itself. I’ve collected hundreds of photo books and tried to teach myself the history of those on whose shoulders we all stand.

I’ve photographed aircraft and ships, birds and bears. I’ve shot tiny things very close to my lens, and massive things many light years away. I’ve photographed football games and motor races, events and happenings. I’ve stacked images for light gathering, and stacked images for focus. I’ve taken pictures that were captured in 1/8000 of a second, and made other pictures that took many hours of exposure (my longest, to date, was around 17 hours).

I even found myself the sole photographer at my old boss' memorial, watching Coldplay, Norah Jones, and others celebrate the life of one of the true visionaries…

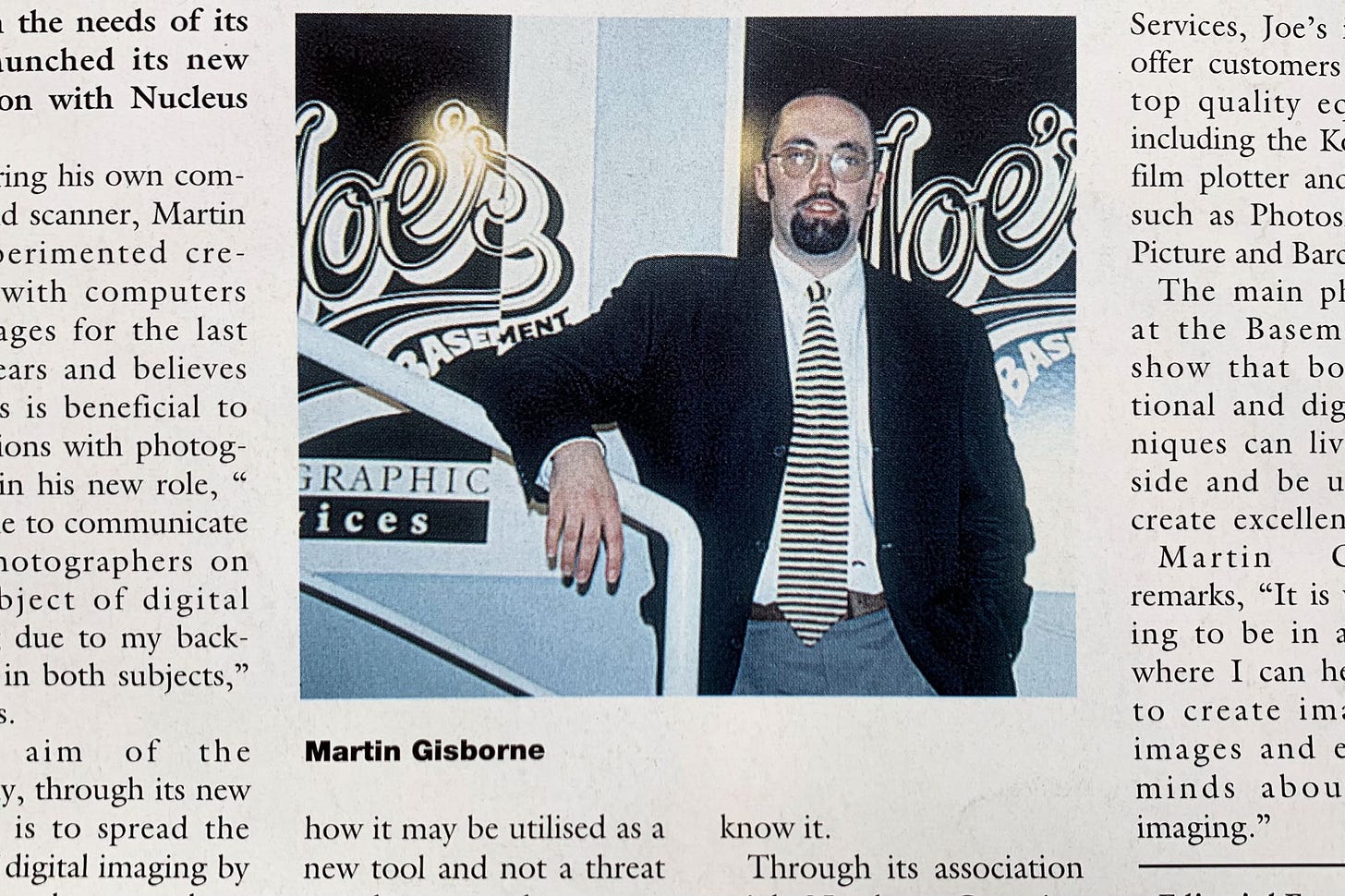

After a spidery crawl of a career path it was, eventually, photography that lead me into the most satisfying period of my work life. Working in the world of photography–not just as a photographer but as someone with knowledge about photography –has opened doors I never imagined possible. I’ve been to three Olympic Games, the Pentagon, and the US capitol. I’ve talked photography in the jungles of Cambodia, on the steps of the Sydney Opera House, the shores of the Bosporous, and in the streets of Beijing. In 2008 alone I spent over 160 nights in hotels, all over the world, talking photography with people everywhere.

I’ve loved meeting, watching, and getting to know some of the greatest photographers, people whose work I’ve admired for many years. I’ve been incredibly fortunate, in that regard.

My timeline in photography has carried me from the purely analog world, through the exciting (but difficult) transition to digital imaging. In fact it’s also been over thirty years since I stepped into the world of professional digital photography, retouching scanned images with Photostyler and the very first versions of Photoshop. Of course there were virtually no digital cameras, although medium format “scanning” backs were starting to appear6.

And now everyone has an incredible camera in their pocket. It could even be said that I’ve played a small role in that transition, working at Apple on their professional photography software, and then later with the photo applications engineering team as their “in-house” photography guy.

What a ride!

I sometimes wonder why I remain curious about making photographs, after all these frames, and all of these years7. Another quote, attributed to American photographer Garry Winogrand, perhaps sums it up best:

“I have a burning desire to see what things look like photographed by me.”

Hopefully, in a dum spiro spero8 kind of way I will have this desire–and the eyeballs–for a few more years to come.

So, yes, 50 years… and counting. Onwards.

Amazingly kids were bought–and encouraged to use–chemistry sets that, today, seem, inadvisable? This looks like the one we had, and it contained a little paraffin burner, test tubes of various chemicals, and a booklet of experiments. Which is all well and good as long as you carefully follow those instructions, but a childs’ curiosity can lead to “I wonder what happens if we… “. I have a vivid memory of blowing something up, in the kitchen, the stains of which remained visible for a few years.

Honestly, I have no idea why we had loose leaf tea except that I was told it was “better”

Technically the Brownie 127 had a 64mm ƒ/14 meniscus lens and a 1/50th second rotary shutter

Drrrrrrrrrrrrrum-na-drrrrrock-it! It’s just fun to say.

My mum didn’t have a camera, and I think she preferred a sketchpad and pencils at home. I came to realize, much later in life, that her coloured pencils set–which I also used–was actually a Stabilo print tinting set, presumably dads.

Scanning backs could only be used for studio still life photography because the camera essentially took three separate “scans” of the image, one for each colour channel. They needed special flicker-free lighting, and cost an arm and a leg.

My master drive contains nearly 14TB of just digital imagery, shot over the past 25 years. I also have a filing cabinet full of transparencies, negatives, and contact sheets.

“While I breathe, I hope”

I have a collection of cameras but not all of them have a personal story behind them. I love that you have cameras that means something to you. I love that you know the history behind them. You’re a very engaging writer. Thank you for sharing this.

Thanks for sharing your story, Martin. What a career!